Not all patients are ready to discuss their prognosis soon after a diagnosis of advanced breast cancer (ABC) – and that is their choice – but the earlier this is discussed the more influence patients can have on their treatment plan and end of life options. Oncologists are not necessarily starting the conversations early enough but it is important that they do, taking into account their patients’ values and preferences. So, how do oncologists provide prognostic information to their patients, and how useful and accurate is the information when given? At the recent ABC7 international advanced breast cancer conference, Dr Belinda Kiely provided information from an oncologist’s perspective, and highlighted some useful tools for patients to consider when having these important conversations. Here's BCAC’s report on her talk:

Sharing prognostic information – what your oncologist can tell you

Dr Belinda Kiely, University of Sydney, Australia

One of the most important discussions between a patient with advanced breast cancer (ABC) and their oncologist is about survival times. This should be started as early as possible, says Dr Belinda Kiely, an oncologist from Sydney, Australia, and should be an ongoing conversation.

Oncologists are not initiating the conversation early enough

So when do oncologists think the conversation about prognosis should be begun? In a study of 206 medical oncologists from New Zealand and Australia, the vast majority of doctors would ‘always or usually’ discuss survival time when a patient asks (98%), or when no further systemic therapy is planned (91%) [1]. A significant number would initiate the discussion when a patient had less than a year or less than 6 months to live – but Dr Kiely argues that this may be too late for some patients to make important decisions. Oncologists should offer the discussion early and, if the patient is not yet ready, revisit it later. Appointments to discuss scan results are also good opportunities to discuss prognosis, particularly if the cancer has progressed, and even if there is another treatment to move onto.

Question prompt lists are useful

Question prompt lists are a good way to start the discussion – particularly if oncologists are aware of these and endorse them. Studies show that these lists significantly increase the number of questions that patients ask [2-5], but that they are not being used as often as they could be. It may be useful to look at a prompt list like the one shown here, not necessarily to ask all the questions but to have an idea of what you may want to ask you oncologist.

Question prompt list for people with advanced cancer [6]

Questions about the cancer and its treatment:

• Will this cancer shorten my life?

• How long can I expect to live? Is it possible to give me a time frame?

• What is the best-case scenario? What is the worst-case scenario?

• What options are available to treat my cancer?

• How likely is it that these treatments will control my cancer?

• If the treatment works, will I live longer?

Questions about end-of-life or palliative care:

• When would it be helpful for me to see someone from the palliative care team?

• Should I consider stopping anti-cancer treatments now and focus more on treatments to make me feel better?

• What can I expect to be able to do in the future?

• Is there a way to plan and document my wishes for care at the end of life?

• Should I appoint someone to make medical decision on my behalf if I am too unwell to speak for myself?

• How can I make sure that others involved in my care know my wishes?

What kind of prognostic information can oncologists provide, and how accurate is it?

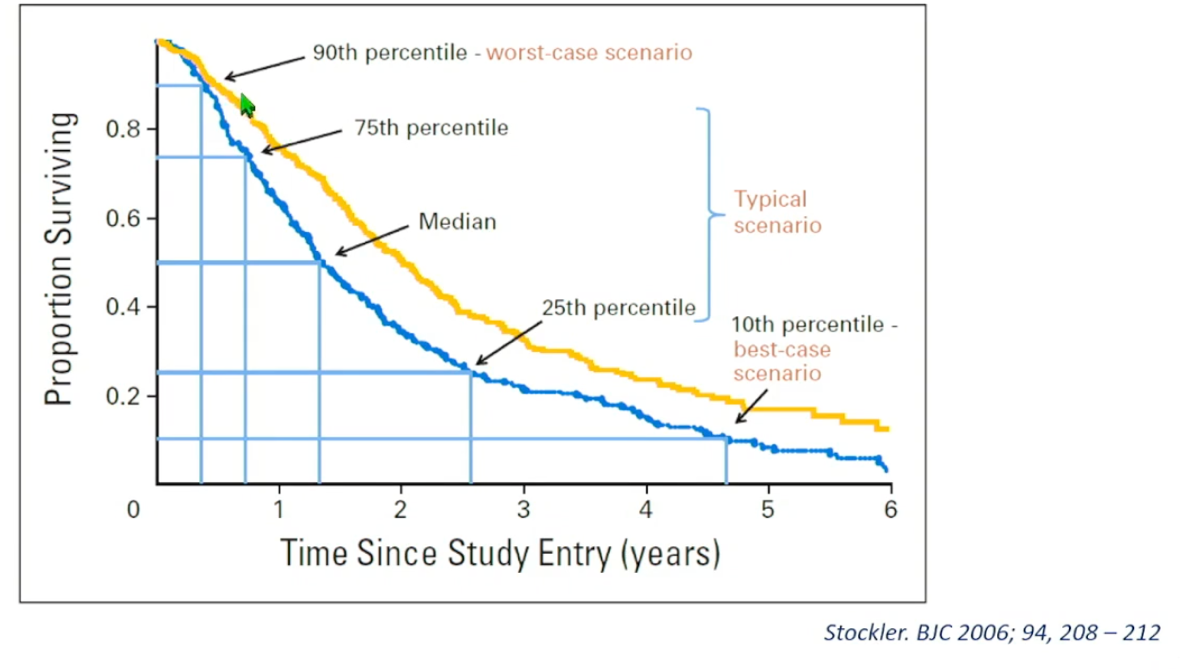

First, not all patients want the same amount or type of information, or at the same time. Your oncologist should therefore be checking in at various time points. Second, oncologists can present the information in different ways. Survival times are commonly presented as a single point estimate, such as median survival time (e.g., median 1 year = half of patients will live beyond 1 year and half will not). This is not always the most helpful for the patient or the most accurate. The other method is to present three scenarios. For example, “if there are 100 patients in this situation, the middle 50 would live for 6 months to 2 years, 5 to 10 would live only 3 months, and 5 to 10 would live longer than 3 years”. The second method can also be presented as a survival curve (see below) [7]. Dr Kiely and her team have developed a website where oncologists can generate survival curves for their patients to help explain the three different scenarios on an individualised basis: www.ctc.usyd.edu.au/3scenarios. When the three scenarios option is used, it has been found to be more accurate than the median survival estimate, perhaps not surprisingly.

Other sources of survival data – clinical trials and the internet

Clinical trials are another source that oncologists use to predict survival times for patients, but there are limitations to these as there are strict rules on which patients are included, meaning they don’t always translate to the reality of the clinic. Many patients use the internet to search for survival times for their type of cancer; this can also provide very unrealistic information. For people who wish to google, there is a more reliable website based on SEER results: https://cancersurvivalrates.com. (SEER is the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the US National Cancer Institute). It is advisable to discuss SEER results with your oncologist.

Discussing end of life care

Conversations about end of life care are not just about practical issues such as type of physical care – they are about what a patient values and what is important to them for the remainder of their life, including independence and how they want to fill their time. These conversations should also be initiated early to ensure that whatever treatment plan is followed fulfils the patient’s wishes. Advance care planning is part of this, and ensures that a patient’s preferences are considered and shared with family and friends. This process may include identifying a personal representative. It is easier to start a conversation about end of life care preferences if the expected prognosis has already been discussed.

Prognosis discussions and long-term survival

With more ABC patients living for longer, the conversations around prognosis are evolving and more research needs to be done to ensure that oncologists and their patients are having the most useful and realistic discussions possible. There also needs to be more research into different cultural perspectives on survival times and end of life priorities.

References

1. Vasista A, et al. Communicating prognostic information: what do oncologists think patients with incurable cancer should be told? Intern Med J. 2020 Jan 6.

2. Brown R, et al. Promoting patient participation in the cancer consultation: evaluation of a prompt sheet and coaching in question-asking. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(1-2):242-8.

3. Brown RF, et al. Promoting patient participation and shortening cancer consultations: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(9):1273-9.

4. Butow P, et al. Cancer consultation preparation package: changing patients but not physicians is not enough. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(21):4401-9.

5. Clayton JM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Feb 20;25(6):715-23.

6. Walczak A, et al. A question prompt list for patients with advanced cancer in the final year of life: development and cross-cultural evaluation. Palliat Med. 2013; 27(8):779-88.

7. Stockler MR, et al. Disarming the guarded prognosis: predicting survival in newly referred patients with incurable cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(2):208-12.

Marion Barnett

29 November 2023